Modules occupy a strange place in the hobby: they have been here since the earliest days of the game, but were relegated to a specific niche within it as time went on. In my experience of learning TTRPGs in the early 2000s, modules were the purview of a particular kind of Dungeon Master; they weren’t something we used to fill in the blanks of an evening, but were considered an altogether different way to run the game. You were either a “Module DM” or you were a “Homebrew DM”, and for some the two never mixed.

Sure, I picked up a few modules up in my time as a Pathfinder 1st Edition Game Master, but I never actually ran anything from them. Instead I would trawl for clever mechanics and scenarios to rip out and sprinkle in my own game as needed - divorced from their original narrative moorings1. I was not interested in studying these books, their characters, and either adapting their lore for my game, or playing in that setting. The benefit to their use was the DM had a complete guide that provided all the lore, quests, and NPCs he or she could want without having to think of them yourself. In fact, these scenarios were so elaborate that I could see no way to memorize them without significant work or otherwise meaningfully incorporate it all into my game.

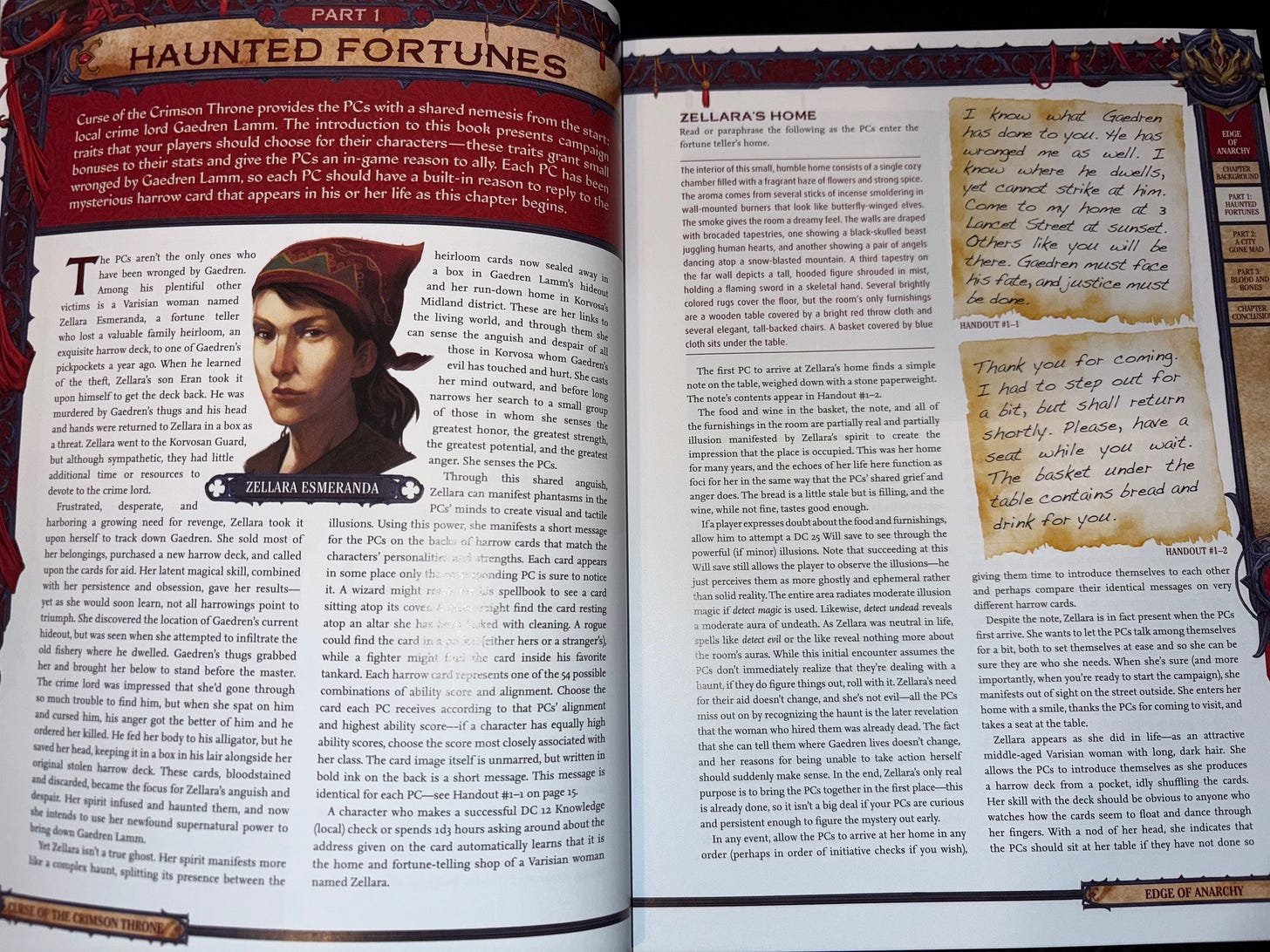

The modern module is thick with descriptive flourishes, NPC portraits, and a high quality presentation…however, these descriptions are so dense - and the outcomes so tightly controlled - the above excerpt is part of a continuous sequence that goes on for an additional 12 pages, with the majority of the text being descriptions of locales and characters, before ending in a battle that the book choreographs for the DM. The book itself does not have a map of Korvosa by which the DM or the players can orient themselves with; this pieces must be downloaded separately and does not appear to be intended to guide play, but is more like a prop to help the players better picture the drama of the stageplay.

The map is far too large, the text far too small, and there is no map key or indicators of locations. The city is meant to be experienced as the story continues, not at the discretion of the players.

Similarly in Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition through 5th edition, Adventures come in large books that corral the players along the story path to the finale. These adventurers are perhaps a bit less egregious than their Pathfinder counterparts, but nonetheless they fall into similar enough patterns that the distinction between “Module DM” and “Homebrew DM” remains.

What Were Modules?

In the introduction to Keep on the Borderlands, Gary Gygax describes the titular keep as “a microcosm, a world in miniature” and that “As you build the campaign setting, you can use this module as a guide”. At the time, it seems that the intended use of pre-written adventures was as a learning tool that the new DM would use to not only learn to play the game at a basic level, but also how to conduct a Campaign of their own.

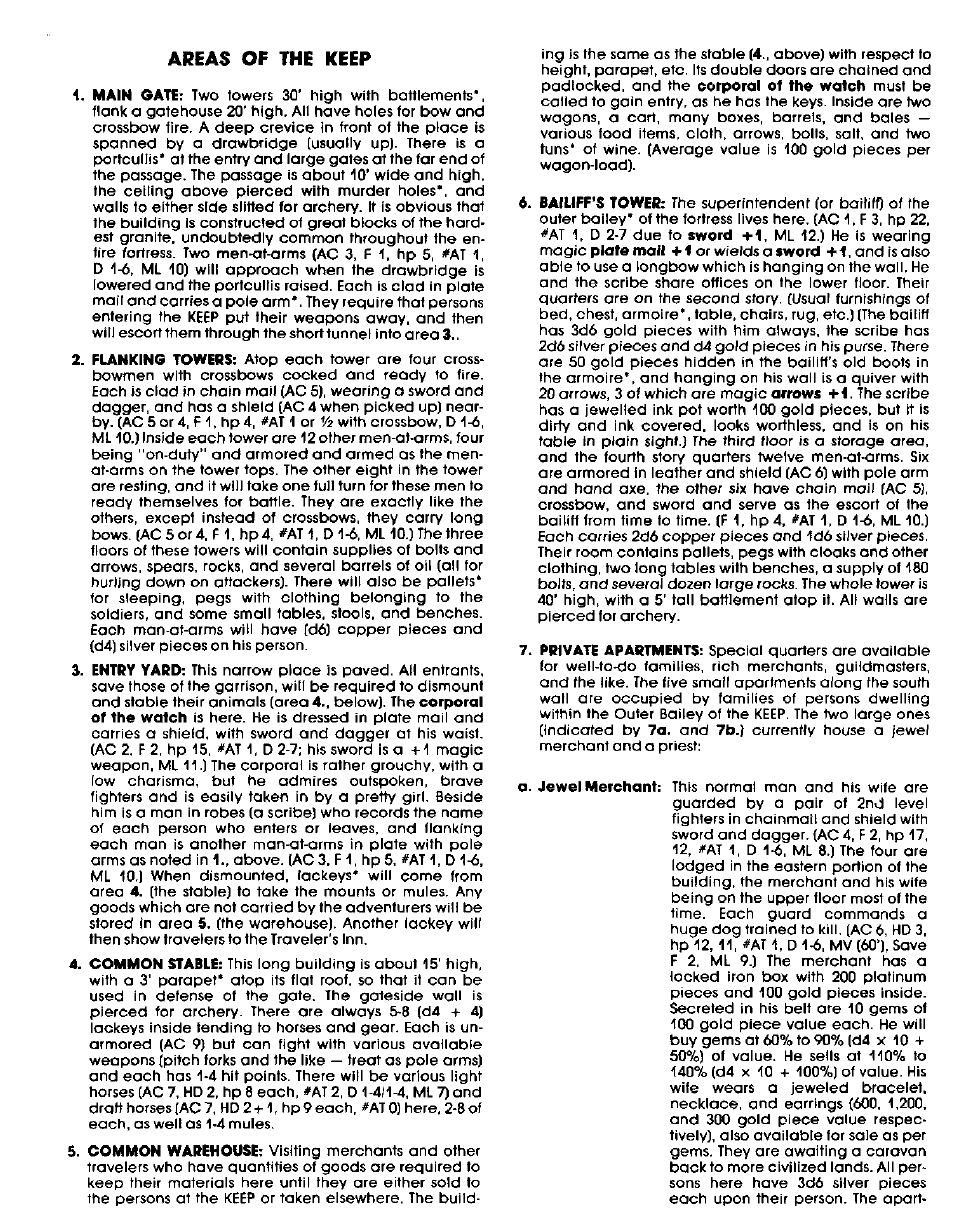

The book has surprisingly few pages, at least compared to what I’m used to, but are packed tightly with information that the DM can easily use to adjudicate the actions of even a larger group. The excerpt below gives the reader an idea of what I mean:

The book continues on like this for the majority of its contents. In almost its entirety, it is easily-digestible descriptions of locations and possible loot. There is minimal expository talk, and no reference to acts or chapters - the players are simply presented with the keep and told that adventurers go there to make their fortune and prevent Chaos from overcoming Law. The only notable “event”-type instructions are instructing the DM on how certain NPCs would react to certain outcomes. If the players do something heroic in service of the keep then they are trusted enough to meet the Castellan, if they team up with the secret traitor in the keep then the traitor will betray them when it would be most opportune to do so at the Caves of Chaos, and so on.

If you don’t own Keep on the Borderlands I highly recommend picking up a copy and flipping through it. It is the quintessential training module; it teaches a greenhorn Dungeon Master exactly what to focus on for a successful adventure for a group of players and experiencing it teaches the players how to interact with the game as refereed by their Dungeon Master. What’s more, it is entirely possible to run the scenario from the book without serious study, which is ideal for the target demographic - a new DM will have their hands full trying to digest the rules after all, so an adventure that works right off the shelf is a huge help. Adventures can become more complex when the DM has a better grasp of the rules.

What Did Modules Become?

With the commercialization of Dungeons & Dragons, TSR discovered that they had a way to continue to generate revenue after their customers had purchased the three core rulebooks. Instead of running one or two and then creating your own, they’d prefer if you bought as many modules as they could publish.

Obviously modules predate Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, but it seems to be roughly accepted that the purpose of those pre-written adventures started as one thing and became another over the course of AD&D’s life. I do not begrudge a for-profit corporation its desire to make money, but I do think it’s unfortunate that modules would begin as training materials for a healthy home game, only to become a crutch that DMs preferred not to do without. I’ve made this clear elsewhere, but I desire a return to the clubhouse model - so of course I would frown at the effects of commercialization…after all, hooking DMs on a product that is so specific in its parameters enabled the slopification of the hobby and facilitated the disintegration of the clubs that the original members of the hobby built their empires on. I don’t lay the blame solely on Corporate Suits mind you, but I don’t believe they’re blameless either.

How Do *I* Use Modules?

Contemporary pre-written adventures are difficult to integrate if you are not dedicated to their use, but the original adventures are still useful to the DM of today and can be dropped in a world almost anywhere with little friction. Whether or not you play Basic/Expert Dungeons & Dragons, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, or any later edition, the adventures that Gary Gygax and his associates wrote throughout the late ‘70s and the early ‘80s are enlightening since they disclose what the original members of the hobby thought were important details.

Obviously, times change and the people of today are not the people of yesterday, and they won’t be the people of tomorrow. However, I believe the old modules have something to teach us that we can bring to our games even now. If you ran Keep on the Borderlands to completion, then you would have a strong template by which to create your own adventures…from there you would have the ability iterate and innovate, becoming truly proficient and developing the milieu of the Campaign World.

To summarize, you will need:

a cast of NPCs

a home base

rumors

a primary dungeon

a handful of semi-related side quests that contain…

smaller dungeons of no more than a few rooms or a single point on a regional overland map

some treasures

minor villains that can be handled within about 1/3rd of a session

and maybe a list of the valuables in the area for when the Thief inevitably tries to steal something

These are excellent starting points for writing your own adventures and you will be able to expand the details as the needs of your individual players dictate. I do think that the 6 points listed above will cover 90% of what players get up to and the remaining 10% is for you to get creative over or improvise as needed.

What About the Future?

Before I conclude, I want to be clear that I don’t believe the old adventures are good solely by virtue of their age. In fact, in the coming weeks and months I will be trying out some more current publications in my home game at the earliest opportunity. I’ve been late to this particular project2 but I’ve been reading through Black Lodge Games’s The Shucked Oyster, and it seems to me that they’ve innovated in an interesting way on what published adventures can be…but more on this when I actually get the thing to the table. Suffice to say that it does not slot easily into either the older or contemporary categories.

Ultimately, I believe the Campaign reaches its apex when the DM is able to best utilize the rules and develop their own creativity to that end. A lot of lip service is paid to “collaborative storytelling” today, but the way I see it there is little in the way of collaboration: the Dungeon Master creates and the players consume. A proper adventure does not have this dynamic and discovering what the Old Guard did in the beginning and working your way forward is a reliable way for a DM to effectively develop their own milieu: they’ll be able to stand on their own two feet, without relying on Corporate, while the players are able to maximize their agency.

One step closer to a better campaign.

Sadly, these amounted to little more than one-off gimmicks.

Especially since I backed it.

I was going to make a point about how the rise of adventures correllated with fewer players reading the rules, but then I remembered even back in '77 not everyone read them.

As for the Oyster, shuck it, Trebek!